Raining On Eora (Sydney, 2022)

I am Kate Constantine, a concrete Koori, from the big bustling urban metropolis known as the City of Sydney. I am a proud Gadigal woman, mother, and contemporary artist of the Eora Nation. The Eora Nation is made up of 29 clans, and originally the home, it is believed, to 10 separate language groups. This vast nation is bound by the three mighty rivers - the Hawkesbury River to the north; Mobs up that way call it the Darkinjung, The Nepean to the west the Deerubbin and the Georges River to the south Kayimai.

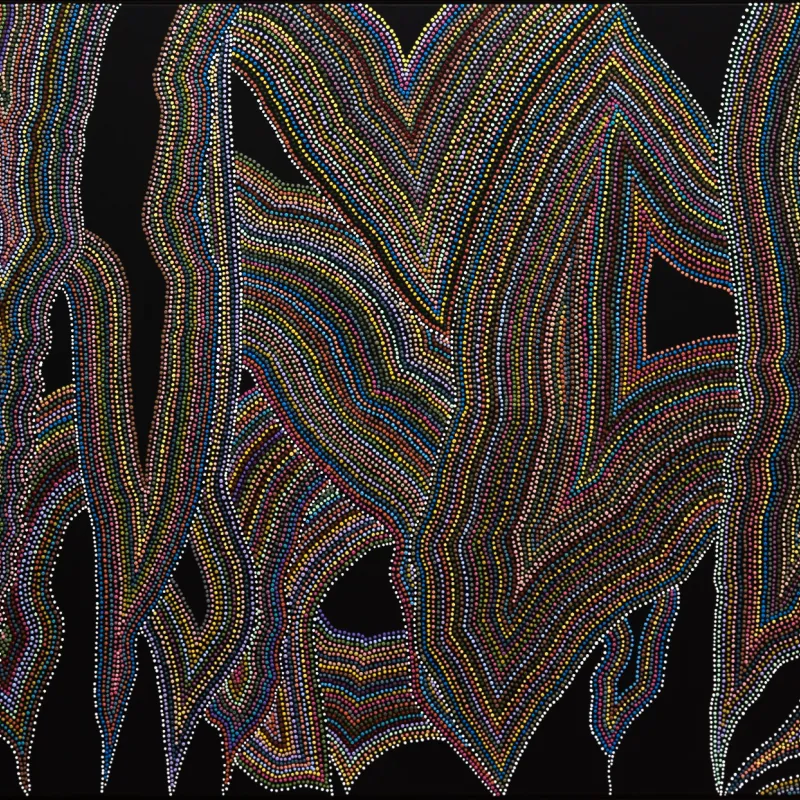

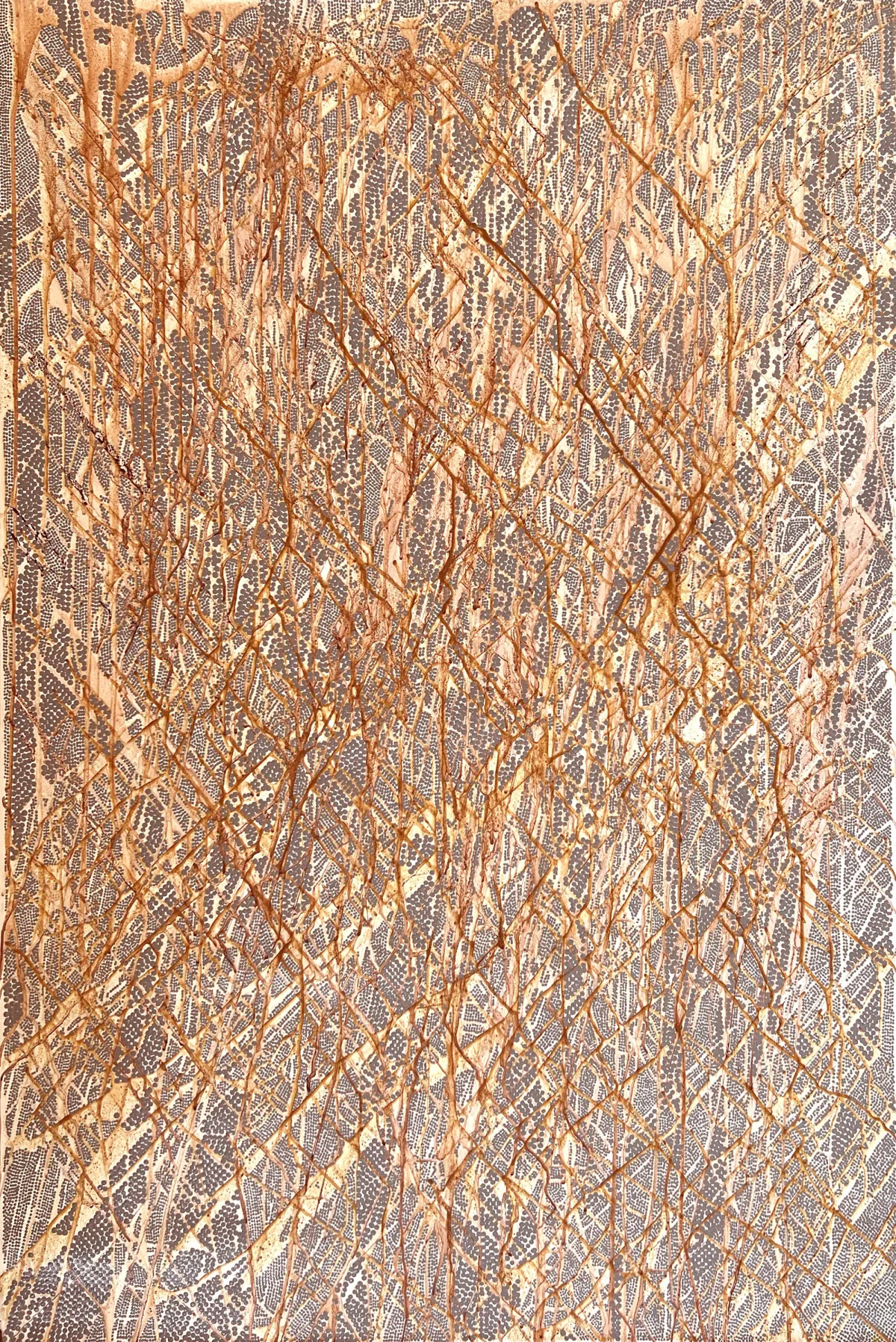

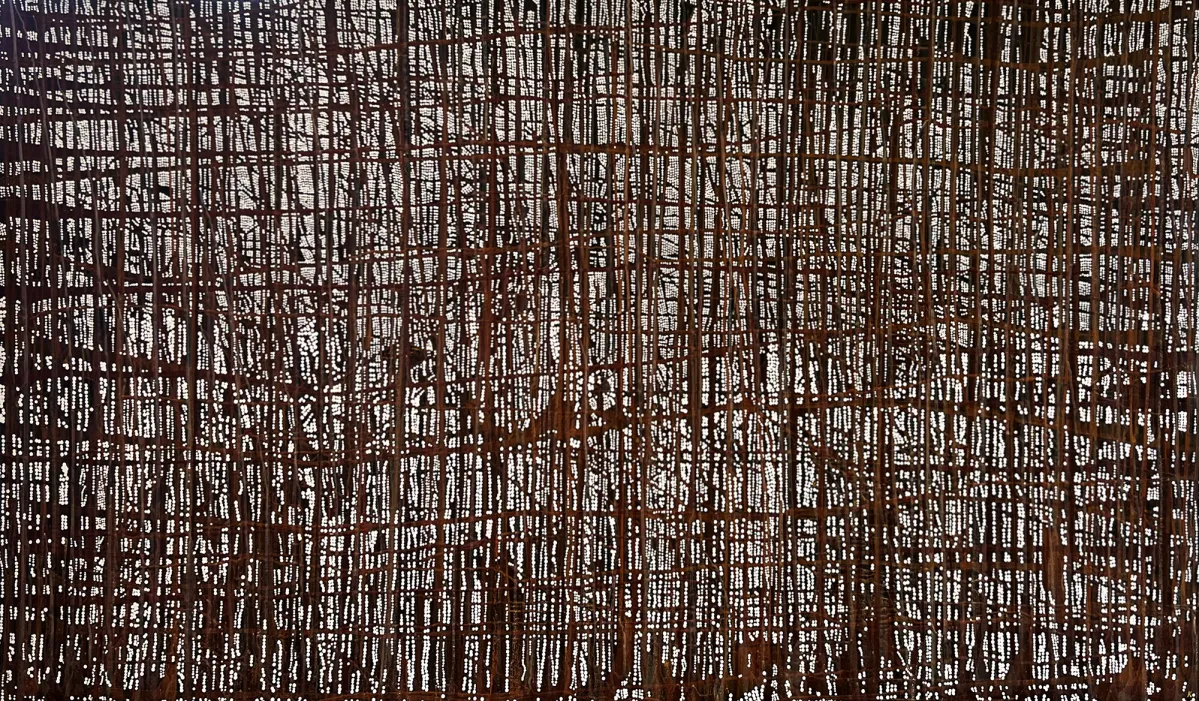

A highly evocative series of Raining Series pieces have been created out of sustainably foraged natural ochres and earth pigments collected on Country. The collection is made up of 10 x large format works created using over 50 layers of ochres foraged in each of the 10 original language groups and named after each clan group accordingly.

The ochres, or the rocks in their most basic visual form, make up part of the rich tapestry of Country. Caring for Country, protecting her, and telling her story is what has driven my insatiable need to bring these works to life.

Combined with the physical collection of the natural ochres and pigments has been a long process of milling these natural elements into dust, sifting and sorting, labelling, and communicating with them. I like to think Country has chosen me to be its Yellamundie (storyteller) for this collection of works. In contemporary Australia there is an insatiable appetite for the sharing of Aboriginal Culture, this is great and honestly the celebration of our Culture is long overdue. Though much more emphasis needs to go into education and truth telling that accompanies that sharing.

The story isn’t always happy, but it is always truth.

This collection has taken almost 2 years to create. A labour of both utter enchantment and absolute soul-destroying devastation for me personally. I have laughed, but mostly I have cried.

This body of work has taken over one thousand hours create. Reading, researching, listening to podcasts, university lectures, being yelled at by construction companies, trusts, charities, speaking with PDH thesis authors, book authors, historians, archaeologists and I have physically grounded myself and sat on each place within Country, silently speaking with our Old People...and these works are what they have asked me to say.

In Sydney, including around Broken Bay and Berowra Creek, a devastating impact from social dislocation, disease, conflict, and dispossession came, almost immediately, with the colonisation of the area. It is for this reason that little first-hand information of the Sydney Aboriginal clans and language structures has survived. The knowledge that is available has been filtered through the eyes of early colonists. Whitewashed.

It should also be remembered that those who did record details of the local Aboriginal Culture also contributed to the destruction of that Culture.

It is widely understood that the Guringai tribe, for which the local Aboriginal clan, the Garigal, were part of roamed lands that ran all the way between Lake Macquarie and the Sydney Basin, therefore Berowra being a central location.

On a recent trip to Country, I was called to Berowra, Berowra Waters to be exact. With nothing to offer Country but myself I walked quietly through the scrub, talking to the trees, and noticing how very occupied the bush felt. Never before have I felt a presence so strong.

The Old People were everywhere!

I was guided to a hidden lookout point that looked to have used by mob for thousands of years. It looked straight up the guts of the mighty Darkinjung (Hawkesbury). I was beckoned to a huge rock crevice and cave no doubt used as a seasonal camp when the seasons were right. The gifts Country gave to me that day were innumerable it felt the least I could do was allow her to share with you her story.

Painted with ochres and natural earth pigments sustainably foraged on this day, this piece of work is Country sharing with you her beauty, scars, truth.

The Frontier Wars of the Darkinjung were some of the most brutal, so many kin lost, and so much greed and degradation. This place is where the most horrific acts of violence, rape, sexual slavery, and depravity occurred unchecked. She has seen it here, and she feels it. But Country; she is still there, and on that Wednesday in December she found me, she sought me out to help show you her spirit.

A story of the first disposed people of not just the Eora Nation but of all Sahul (Australia). We are now few in numbers, but we were once strong, smart, and full of conciliation. We are a resilient mob, tough and memorable, just as our land is. Otherwise, why would the Colonists have abandoned their designated Colonial site at Botany Bay, to have chosen her banks, her clean water stream, her abundant marine food resource to begin one of the world’s most famous cities.

The Gadigal invented the first fishing hook, and commercial fishing, and we had so many different words to describe love, friendship, and honour, that I can only conclude we used our charm and light to continue our Culture then as we do now. We never gave up, instead we learnt to live within the parameters we were dealt, as we continue to do today. Many of our customs, stories and old ways may be gone, but we are not.

Some of the most exciting, exhilarating, and exhausting work I’ve ever produced. Such enormous intensity and measured patience in equal parts as I am Gadigal, and Gadigal is me.

You might know her as Bondi we knew her as Boondi which translated means surf. Or to you she is called Coogee, originally Coojay or the place where seaweed dries, or literal translation “stinking place”. (Bet the real estate agents don’t list that on the brochure).

Whatever name you know her as, Bidjigal Land and the Bidjigal people have always been avid collaborators with my mob, the Gadigal, and those from further away. A hospitable mob who lent their beautiful ocean vistas and plentiful ocean catch to other mob both local and from further afield.

We have all loved Bidjigal Country in some way, and many have called her home over centuries. But it’s little known that the Bondi, Tamarama, Bronte, and Coogee have some of the most amazing free to view Aboriginal rock paintings and engravings of the Eora Nation. You don’t need to go all the way to the desert - they are right there on Bidjigal Country for you all to engage with.

The whale is my favourite and forms a very important part of our Eora Songlines. See if you can find it next-time you’re in the Eastern Suburbs.

She is Wangal and she was not submissive. Her people fought. She has heroes, warriors and above all she stopped migration out of the Waran (Sydney Basin) for years. No mean feat given her clan / language group size was quite small and the enthusiastic zeal exhibited by the colonial military and convicts alike to further conquest land. The aforementioned were indeed starving in the new ‘Colony’ and after the 2 years’ worth of rations had been spent and no new ships arrived from England, they understood that getting past the Wangal to more fertile soils in which to sow crops was a matter of survival.

The ‘food bowl’ of the colony, as it would later be known, meant expanding out from the sand and limestone rock Country of Waran (Sydney) on Gadigal, Cammeraygal and Bidjigal Country was essential for the colonists to survive. The Wangal held strong for years. Think of that; years of hiding, fighting, strategising. The Country sent in Bennelong to try to manage, or perhaps manipulate the new Colonists and protect the people - but we all know how that ended.

Imagine the stress in a small-knit community each day, not knowing if it would their last. Imagine the faith and the hope these people must have had in their hearts and souls to stand strong for such a long period of time. We owe these people our gratitude.

She was fertile Country. She grew many things in her soil and this mob cared for this Country. So much so, that when the colonists came and realised nothing would grow in the rocky ground at Waran they ventured out and renamed the area “the food bowl of the colony”!

It was here that Governor Macquarie coined the name Rose Hill for the Parramatta region. He later decided he liked the Aboriginal name for the place and the People from that place (part of the broader Dharug People); Wallamatta, Burramatta, Parramatta. And hence the confusing name change game of the region began.

It was here that Governor Macquarie set up his second (and preferred) residence.

It was here that the first Aboriginal children were forced from their clans into the first Colonial orphanage for their “betterment”.

It was here that blankets became the irreprehensible commodity exchange; a wool blanket every winter for the taking of land, a wool blanket each winter as payment raping of women, a wool blanket drawn round your shoulders on a cold winters night as payment for the indentured servitude (slavery) of your children.

It was here that all Blak eyewitness accounts talk of being terrified of the “men in the red coats with gold buttons” - the English Military, also known at the time as the Rum Corps.

Indeed, they were so scary because they were military, but they were even more intensely feared as time went on as they owned and controlled the Colony’s almost valuable commodity, not money, nor food.... but rum. Controlling both corporal punishment and the economy (rum) made these men untouchable. It gave them a sense of entitlement that helped to swiftly induce Genocide here on this Country.

It is curious then that Country, our mother offered me up the deepest red ochres and the goldest gold ochres I’ve ever collected to paint this artwork.

I reckon, she wanted me to tell you this yarn.

She is sad, she is sorry, she watched the destruction and could do nothing to stop it.

She sent her woman Barangaroo to Bennelong perhaps to help him in his efforts to infiltrate, appease or manipulate the Colonists. I’m not sure anyone will really understand the true motive for his intense fascination with his oppressors, especially the obsession with the Biyanga (father, but also the term Bennelong gave to Governor Phillip), though many speculate.

Regardless, Barangaroo a strong woman, she spent her days with her clan and rarely entertained the Barawalgal (British) as her husband did. She was deeply shamed at the hands of her husband and Governor Phillip when she was disrobed of a petticoat and humiliated naked in front of large group of military officers who then cut off her hair.

When she passed away years later, that disrespect was further enhanced by her western burial in the front garden of Governor Philips residence, modern day Circular Quay. A practise that is against Cultural Protocol and perhaps shows how enchanted Bennelong had become with his oppressor as to allow this to happen. Or perhaps it is a sign of how controlled he felt by the Biyanga’s (Governor Phillip) power over his Country and People.

It boggles my mind that a 24-hectare plot of land on Gadigal Country near present day Darling Harbour was named after a woman who was not of that part of Country, nor was she married to a man of that part of Country but was shamed, disrespected and ridiculed on that part of Country.

In Aboriginal Culture it is taboo to speak the name of a person who has passed onto the Dreaming. So much so, that other people of the same name must change their name so as not to cause offence or disrespect to the family of the deceased. It follows that this a curious naming convention of an entire foreshore precinct.

Regardless, Cammeraygal, encompassing the land from the lower north shore up to Manly fostered tribesman from neighbouring mobs to ensure safety and security for a long time. They watched on in horror as the Colonists arrived, a front seat to the beginning of the end of a time honoured and mostly peaceful past.

She is staunch.

Many people like to say she doesn’t or never existed. I don’t subscribe to that thought. She is home to up to 40 clans.

She ran interference that is not capable of the modern man.

She stopped the “spread” of the Colony for 25 years. 25 years she kept them away! She was harsh on her people, but they knew how to work with her to make her yield.

As the geographical centre of modern-day Sydney, she is often left in the Harbour City’s wake, but her history is immense and well worth looking up

Whilst not technically a language group of her own (Gweagal people belong to the greater Dharawal Mob), this clan is and has always been of great influence in my life. I spent many of my younger years growing up on this Country and she always sang me her stories.

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered sacred. Historically, clay was used to line the base of canoes so fires could be lit inside, and the day’s catch cooked up fresh for the women (who provided the main source of fishing resource) and children.

Caves and rock shelters are located in various places along the Kayimai (Georges River), which over the years have eroded into the sandstone cliffs. There is a large cave located in Peakhurst with its ceiling blackened from thousands of years’ worth of campfire smoke. There are caves located around Evatt Park, Lugarno with oyster shells ground into the cave floor. A cave has also been discovered near a Baptist church in Lugarno which was found to contain ochre and spearheads set into the floor of the cave when it was excavated. Another cave exists on Mickey's Point, Padstow, which was named after the local Gweagal man. It is thought that the Gweagal clan migrated as far north as Kurnell and west as Liverpool.

This Country feels like my childhood on the Kayimai (Georges River) and is commonly respected as one of the last Sydney Aboriginal frontiers with people living a traditional life up until the early 1900’s.

She is confused.

She has been given too many names, by too many people not of her kin.

She is sister / brother to the Dharug.

She is the northern beaches, she is breath-taking, beautiful and she is subversive.

Upon sitting with Country north of Cammeraygal land and west to the Darkinjung, I became curious with understanding how much Culture remains here. The northern beaches whilst firmly established and bustling hubs of human and built environmental activity - they are still in many ways quite unblemished in parts. This curiosity led me to discover Dennis Foley a Gai-Mariagal man, author, and historian.

“What the Colonists never knew, and still don’t - and this is extremely important - is that we continue to practise our culture even though our numbers are fewer in each generation. Until about 1900, men were still scarified. In 1930-40 the last law with scarification practiced in ceremony, at Belrose and at Wheeler Heights... In the 1960’s women continued to regularly make their pilgrimage to the sea and to fresh water for ceremony, and boys like me were still being trained.” (Foley & Read, 2021, What The Colonists Never Knew).

This extract among others confirms my many suspicions that Cultural Practice did not ever cease, not here on the Guringai / Gai-mariagal part of Country and indeed not anywhere else either. It just went underground.

As the artist it is impossible to detach yourself from your work, and in this case that impossibility is magnified by a million when you’re speaking of your own Country. And as such, the Dharawal part of Country feels irrevocably sad.

She is in trauma.

Many of her decedents are influenced by discredited Caucasian historians the likes of Norman Tindal (1900- 1993), and his wildly contested ‘mapping’ of Aboriginal people and land, not exclusively a Dharawal problem, this extends to work he produced on Groote Eylandt and in South-east Queensland. It’s curious also that Tindale’s “work” with fellow historian Birdsell (1939) to Cape Barren Island Aboriginal reserve led to their advocacy of assimilation ("absorption") as a solution to "the half-caste problem" too. These errors of judgement and misinterpretation leads to a level of social and political unrest.

The Country of the Dharawal was once considered the land from La Perouse to Bundeena and inland until it met its sister mob of the Dharug. But incorrect filtering of information about land and boundaries coupled with advent of the La Perouse mission in the 1880’s; whereby many Aboriginal people residing in the Waran (Sydney) area were rounded up like sheep and shipped onto foreign soil well out of the way of white ‘civilised eyes’ has led to sadness that is palpable.

This rounding up, was exactly that. Executed in military fashion over a quick succession of weeks. All known Aboriginal persons were scooped up unlawfully by the Police and forced to live forever after at the ‘LaPa mission’. I couldn’t even imagine the unrest, people from different mobs, different family and clan groups all squashed in together - because all Aboriginal people are the same right?

My great Nan missed these round up’s. She lived out her life on her Country, Gadigal Land until she died in 1981 the year I was born. She was considered “lucky” to escape the mission. But she housed in her backyard many mish walk-abouts. Those that had run away, escaped for a bit, were taken in by her and her family and given safe sleeping in the backyard by the fire.

There are a lot of politics that are born out of the LaPa mission, but for my part in Dharawal’s story, I would like to consider her a friend, just like my Nan did.

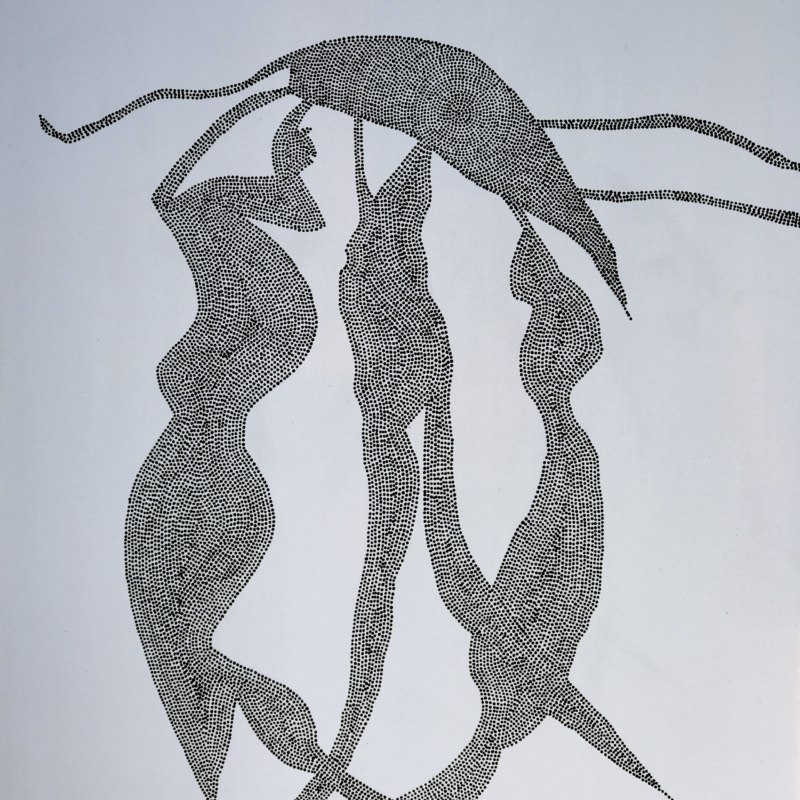

Scarring is like a language of its own, precisely, and ritually inscribed on the body, where each deliberately placed scar tells a story of pain, endurance, identity, status, beauty, courage, sorrow, or grief.

These are the Garanga of my Country. They show me the many effects of Colonisation on Country, its people, its place, its heart, and its soul.