DJIYADI NGUMUN (Sydney, 2023)

This collection is a celebration of the subtleties and subversives that have helped our mob keep our Culture alive. The Gadigal are a proud but graceful people. We choose to share our Culture and our Stories. We stand together with both our Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal brothers and sisters. I hope you find that this collection of works shares truth and beauty in equal measure. Only the truth can set us free.

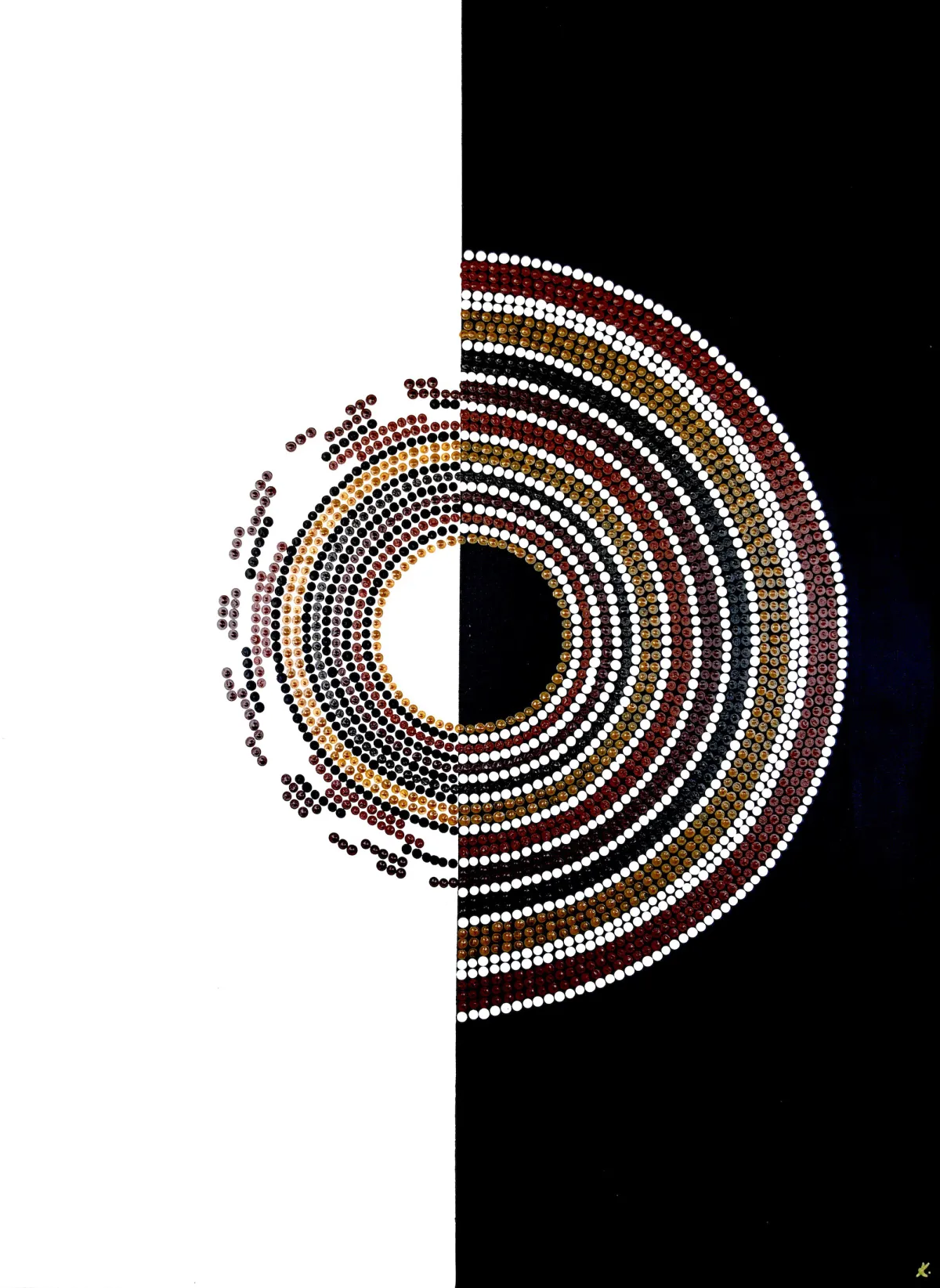

The Caste collection is a series of works where each canvas is brutally divided into fractions or Bioportions of white(ness) and black(ness).

This is to reflect the bigotry and racism that tries to diminish Aboriginal culture in Australia by this notion of diluting the amount of black or ‘Blackness’ in we humans. The collection is hugely inspired by Andrew Bolt and his insatiable need to try and call out Bruce Pascoe (amongst many others), a widely successful Blak Australian of scholarly merit and award, as less than Aboriginal because of their “diluted” heritage. Unfortunately for Bolt and people of his ilk, the attention brought about by the discussion only forces further resolve of those in question and their kin. No dilution of Blak is possible.

The Eora Nation is bound by three mighty rivers; the Hawkesbury to

the north, the Nepean to the west and the Georges River to the south. The Nation is made up of 29 clan groups. The Gadigal, my mob, is the one that occupies this very place – Sydney city. Of these 29 clans it is believed that 11 languages were spoken, and understanding from mob to mob was bridged by family and kinship ties, and largely by marriage.

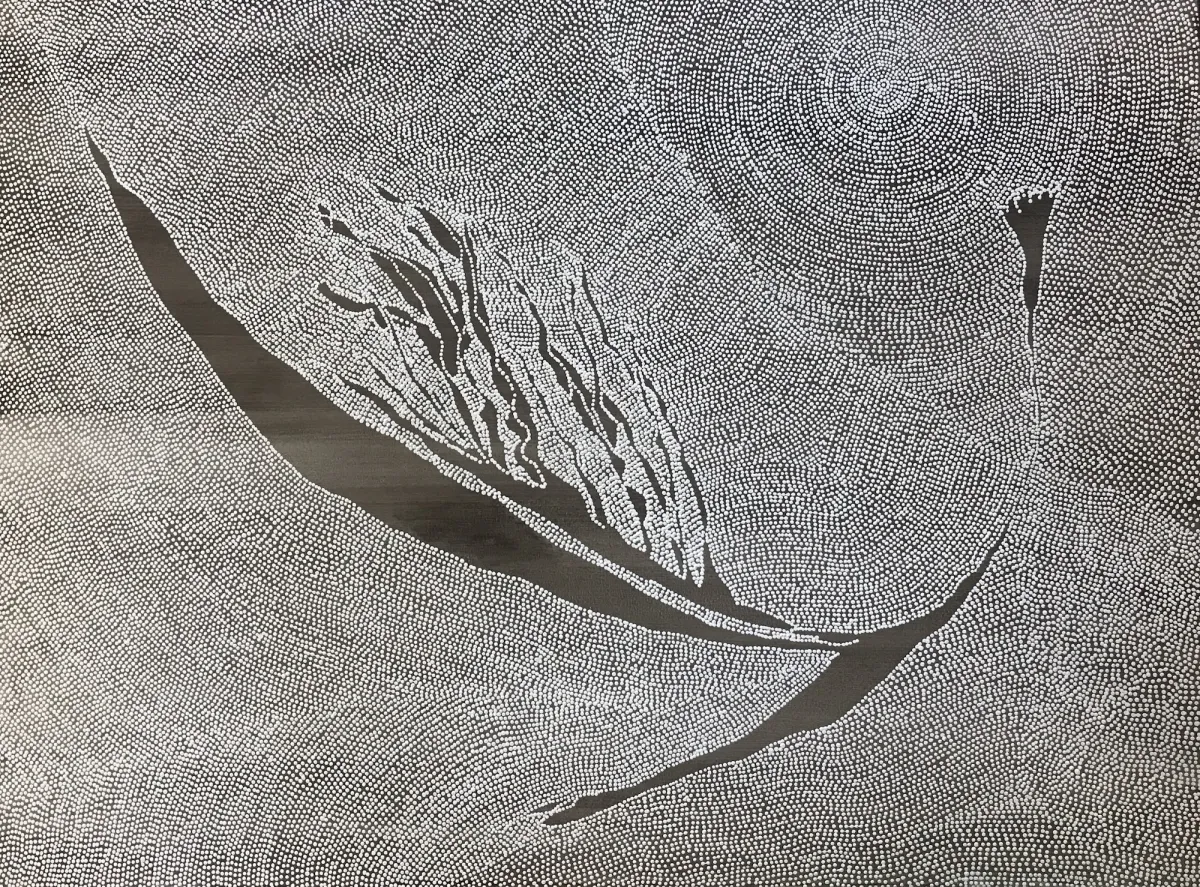

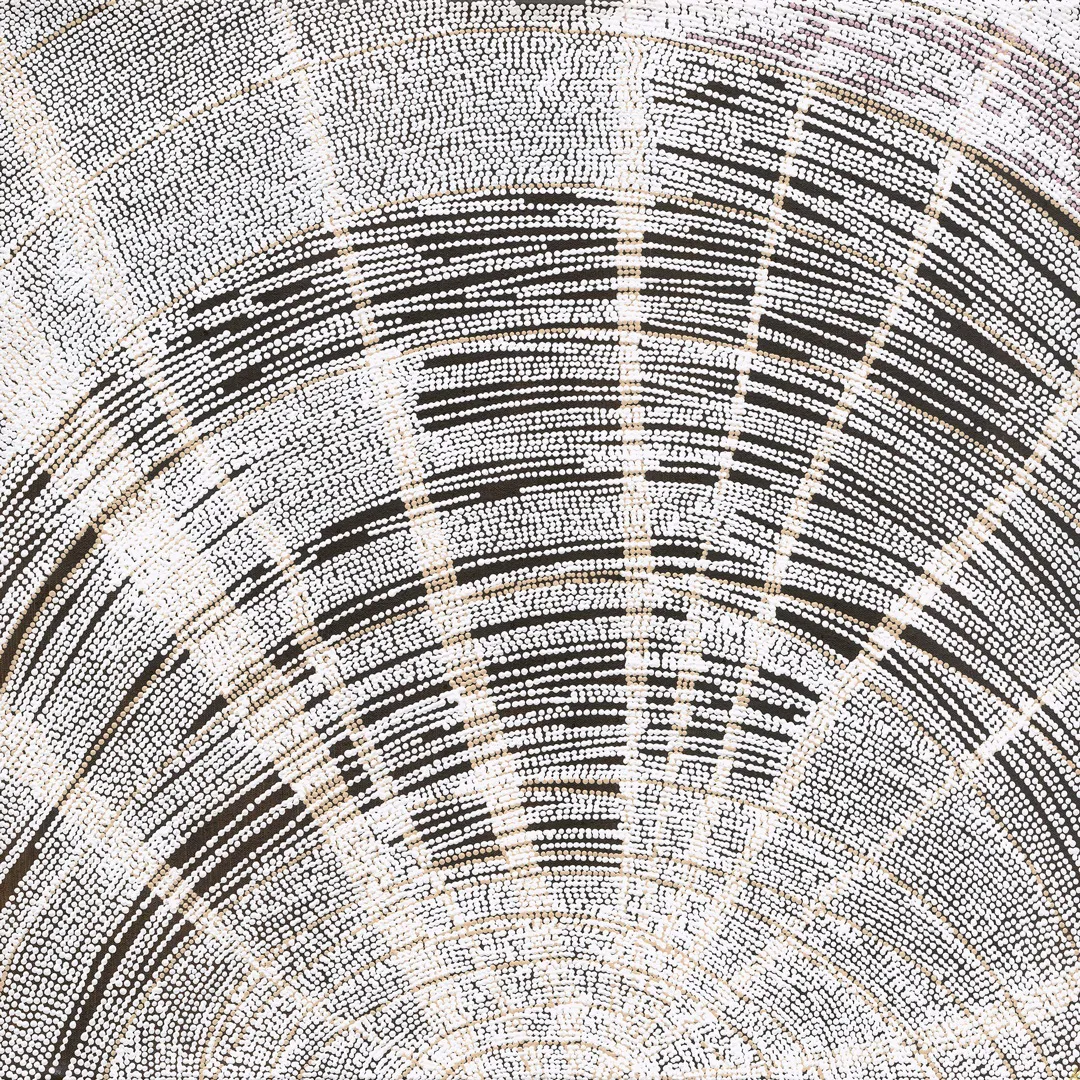

This work depicts the 11 language groups as a tight-ringed and complete circle at the centre; a further 18 rings are worked around the language hub, or core, and in total the 29 rings represent the nations/tribes of Eora, Sydney.

The work is split almost in half, but not quite ... see, at the time of the First Fleet landing it is estimated that 1,500 Aboriginal people lived in Eora, and we know from well-documented archives that only c.1,400 made the journey from England. It was the last time in history where we, the Traditional Owners of this nation, were in greater numbers than our Coloniser.

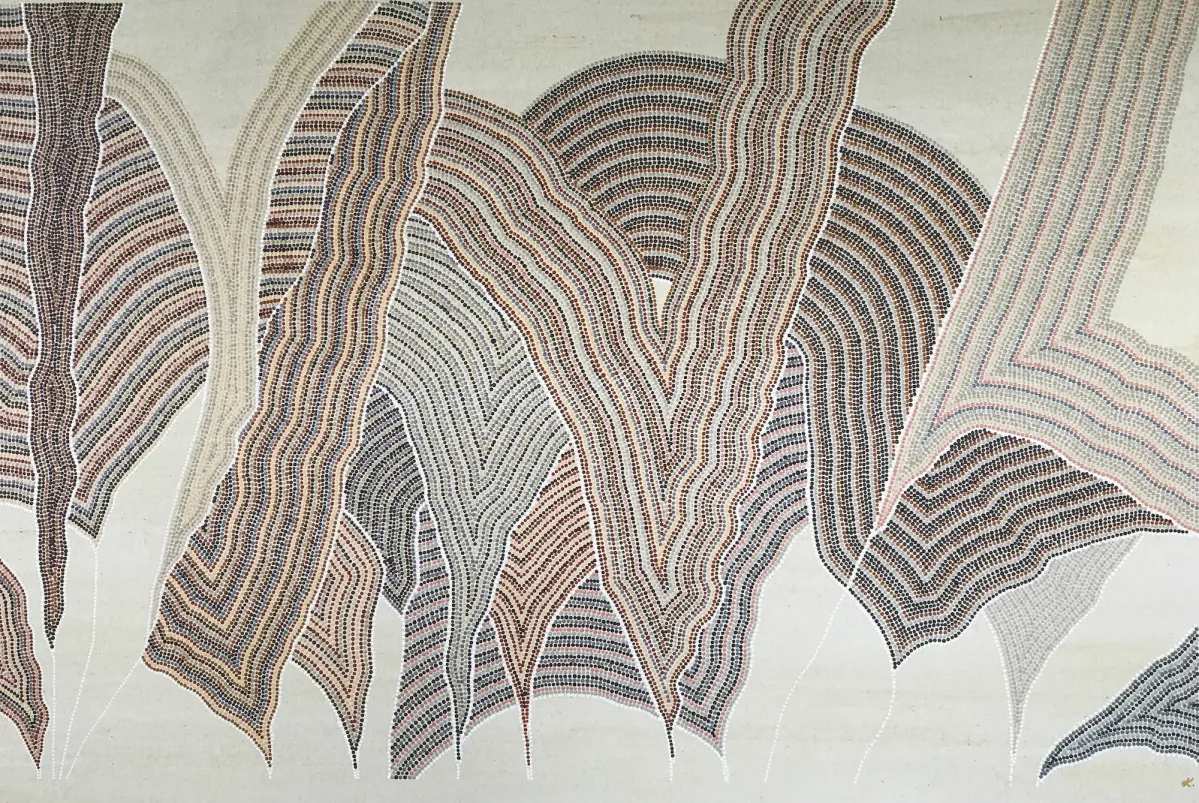

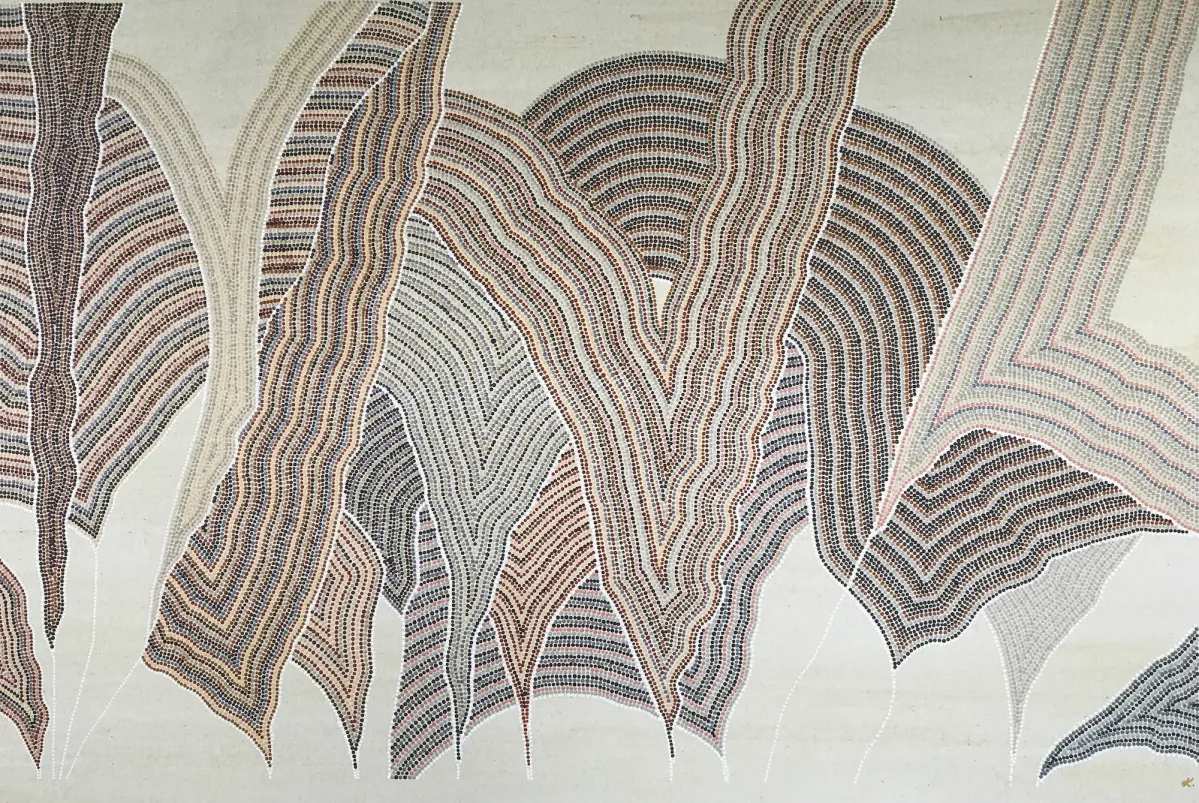

Scarring is like a language of its own, precisely, and ritually inscribed on the body, where each deliberately placed scar tells a story of pain, endurance, identity, status, beauty, courage, sorrow, or grief. These are the Garanga of my Country. They show me the many effects of Colonisation on Country, its people, its place, its heart, and its soul.

Noun

1. A large crowd of people, especially one that is disorderly and intent on causing trouble or violence.

2. The mafia or similar criminal organisation

Verb

Crowd around (someone) or into (a place) in an unruly way. Original owners

Family

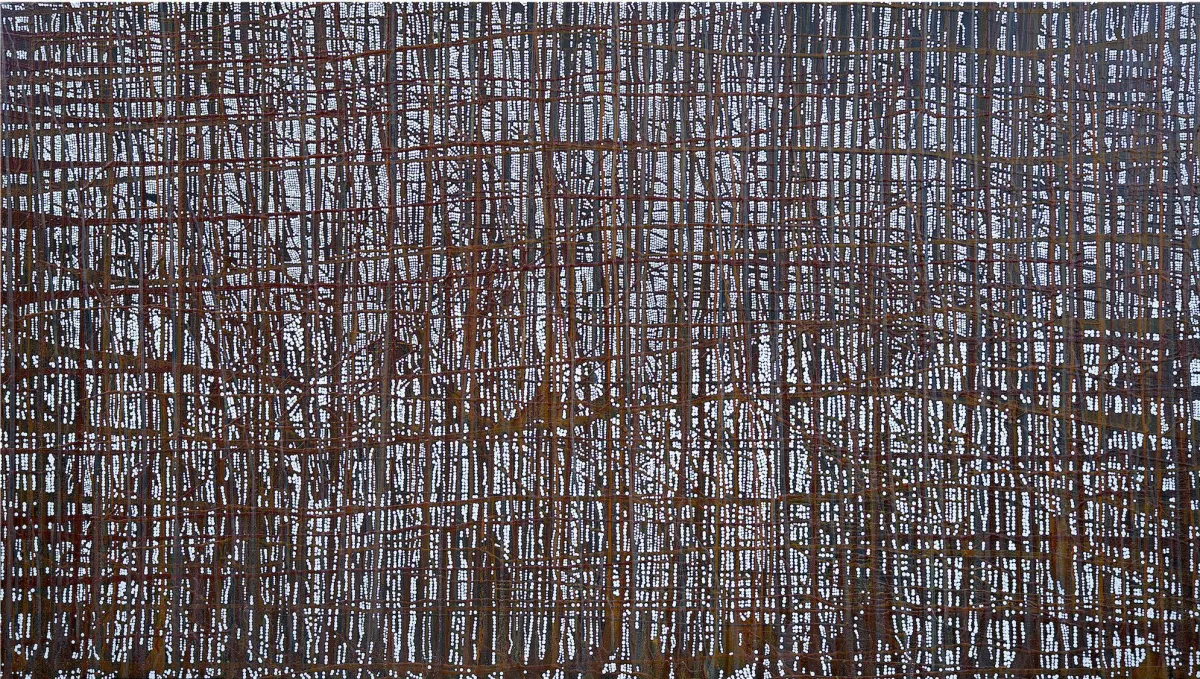

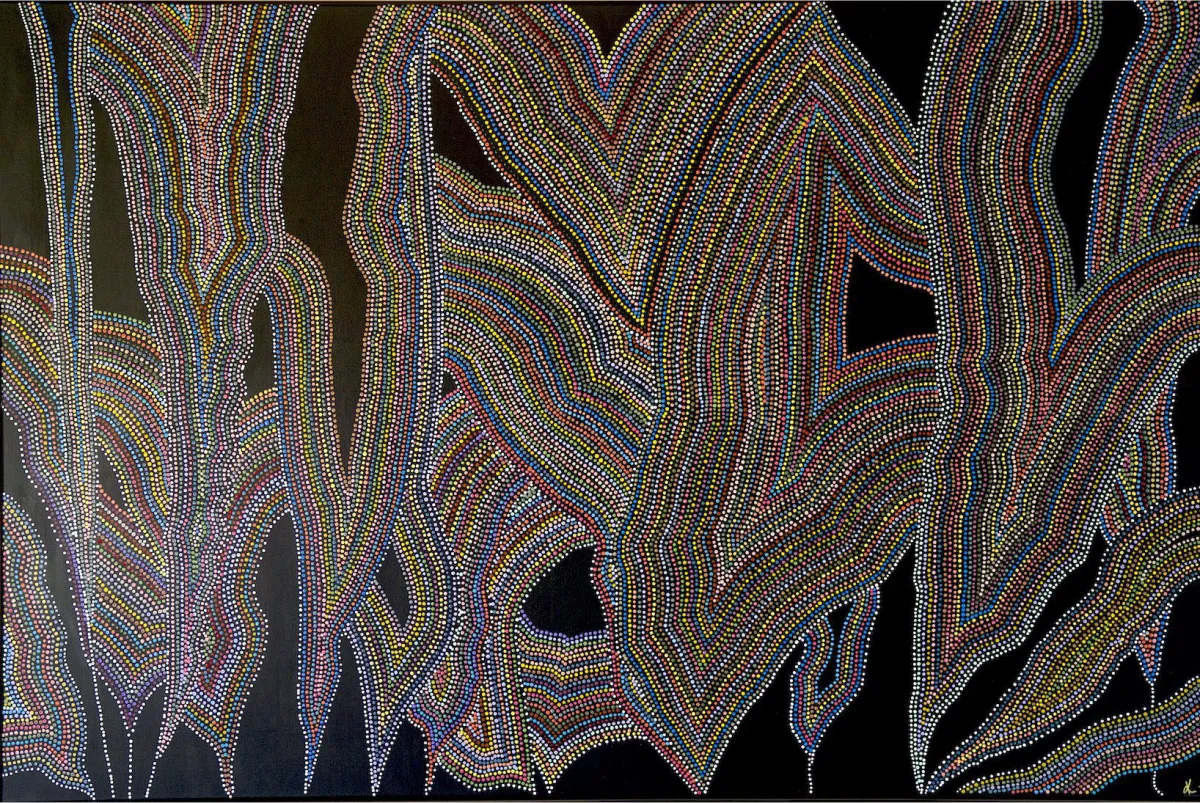

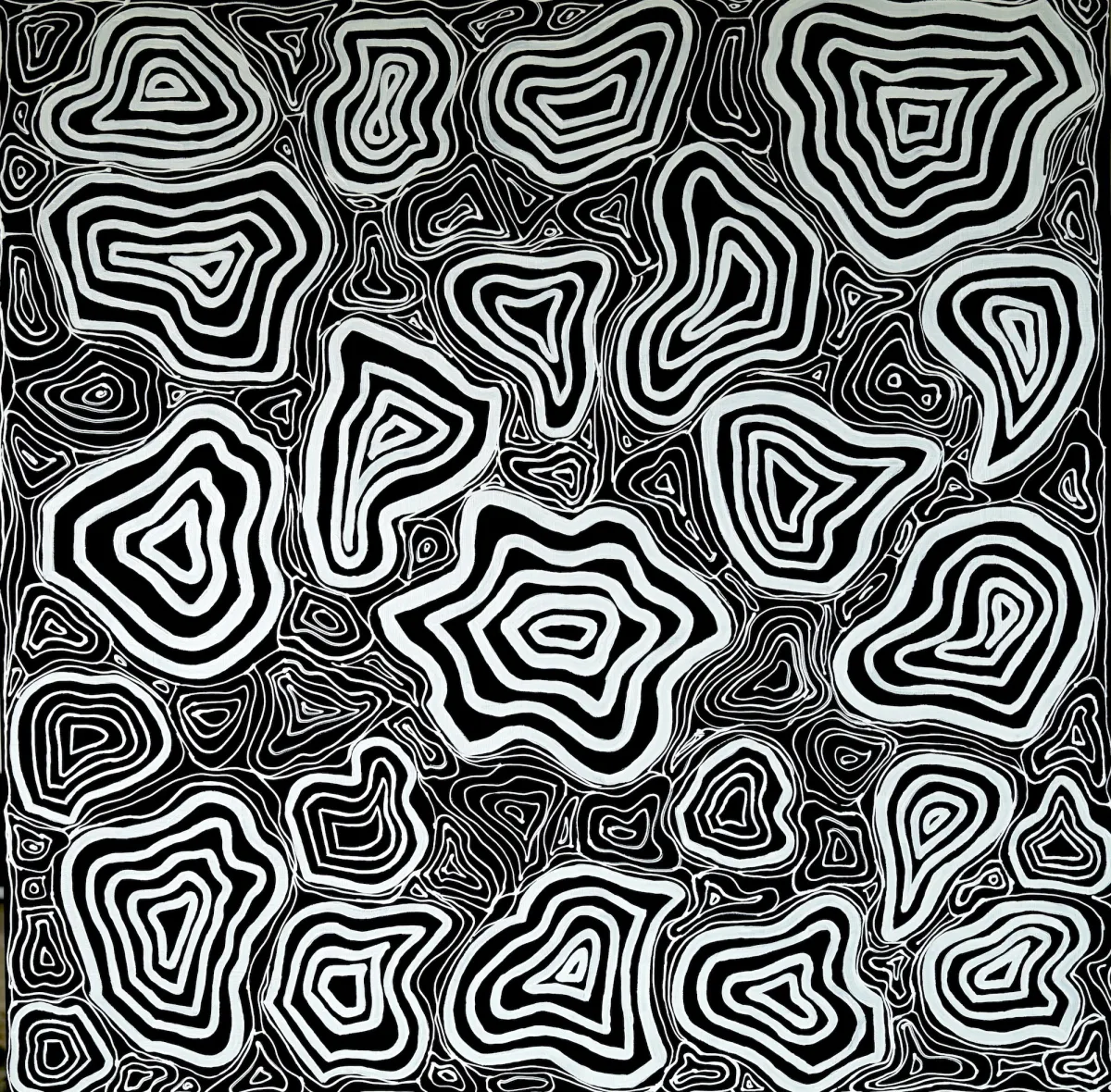

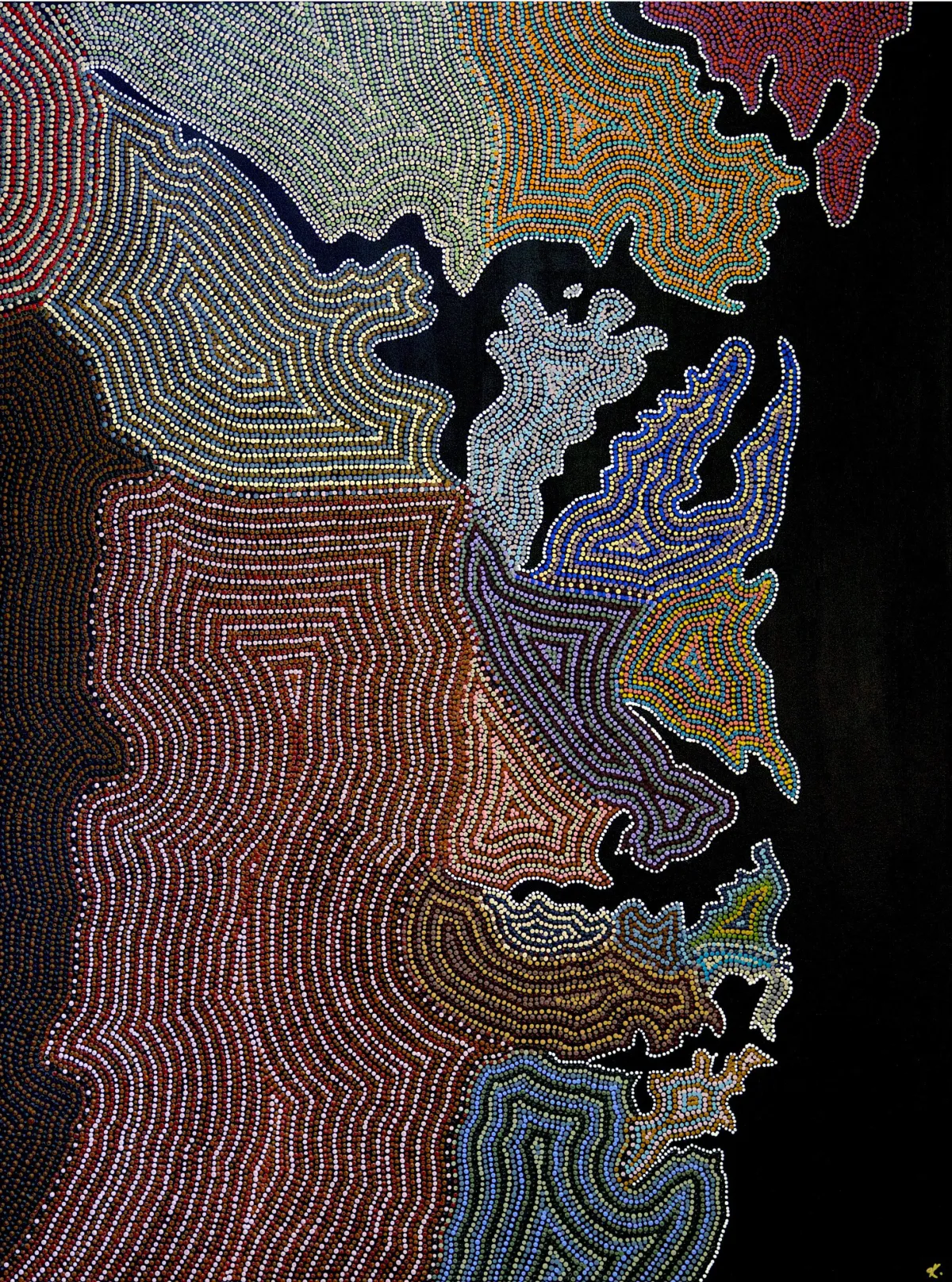

Every line on this piece is as individual as the mob or Language group it represents. This work has referenced the much revered AIATSIS mob map for accuracy. Any errors are mine (the artists) alone. This is the grounding piece for the series Colour Correction

An ode to the 15 language groups of ‘Greater Sydney’. May your resurgence awaken a people to your beauty.

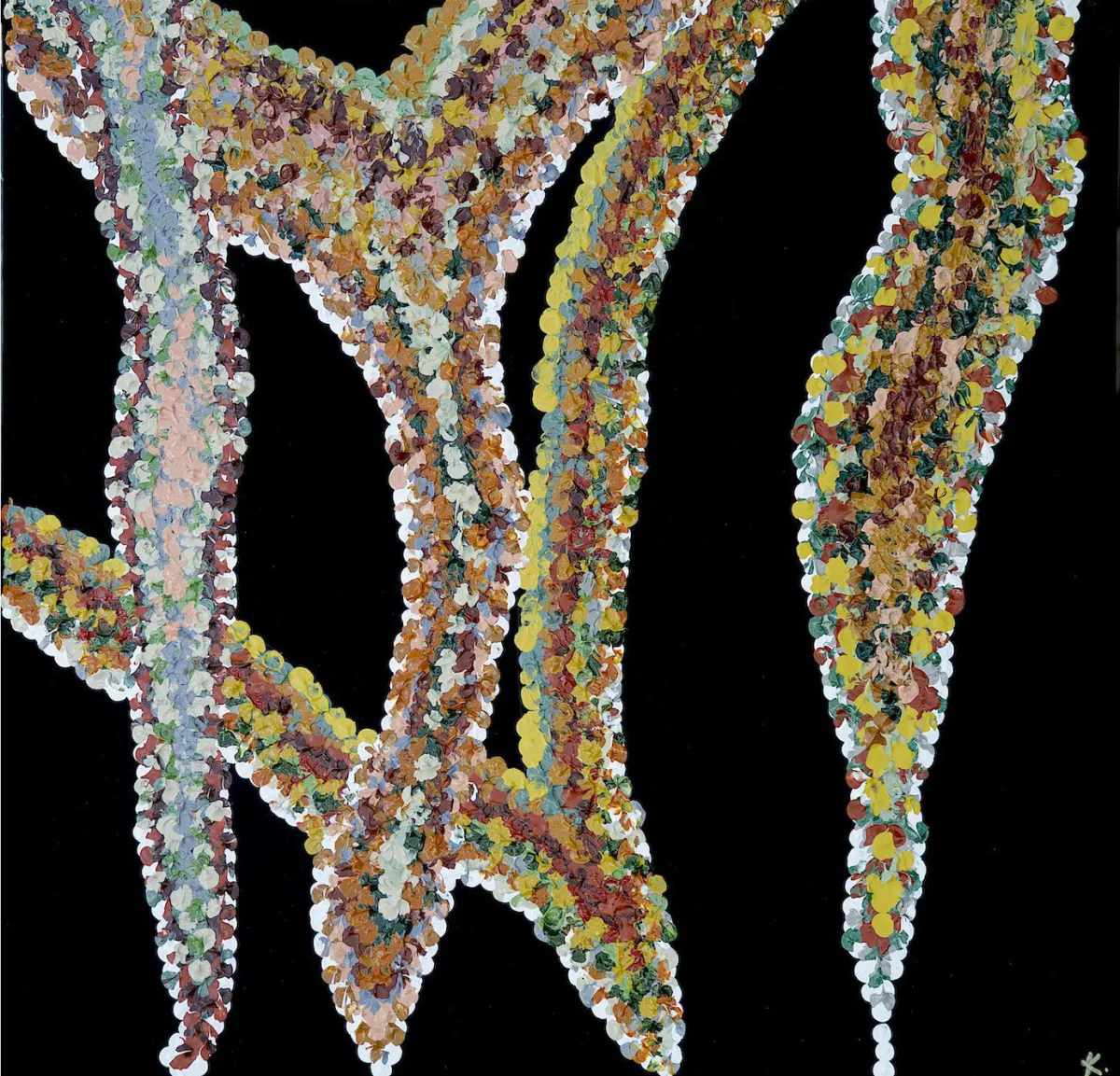

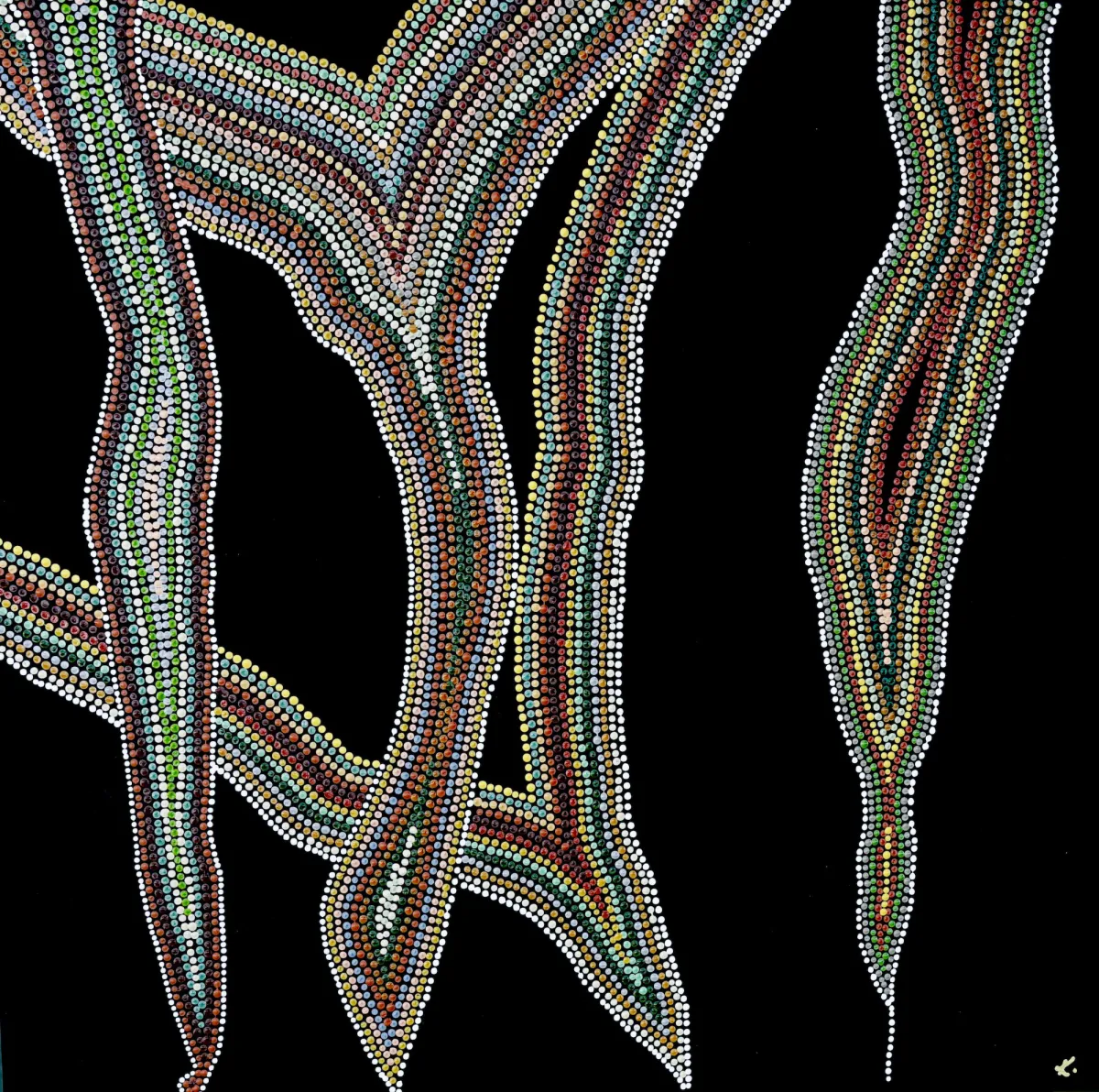

Each ‘cone’ represents each mob of the Eora nation.

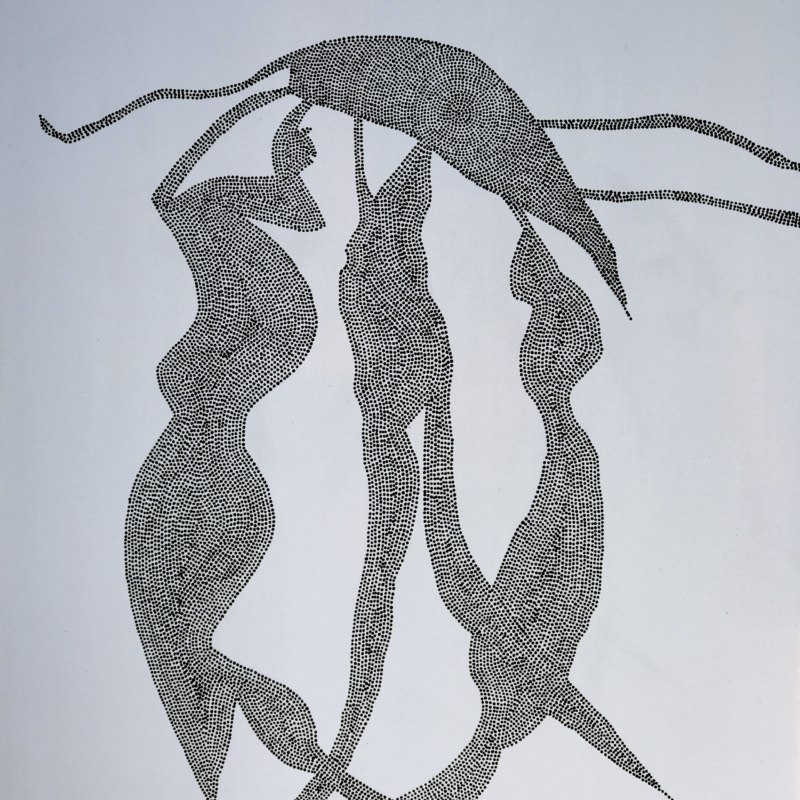

Gadigal women. Strong and few.

Focusing in on our Dyin (women), telling the stories of our matriarchy, the strength, the knowledge, the wisdom and their love.

We come from the smallest kinship post the colony’s inceptions. It’s academically argued that all Gadigal people derive from three people. I’m not sure I believe this, but it goes to show how few our numbers dwindled down to. In spite of such a small kinship, we are Mudung (brave). Showing up is Mudung in a world that doesn’t want us to identify, speaking up is Mudung in a world that doesn’t want to acknowledge and apologise for the wrongs it has done, and saying NO is Mudung.

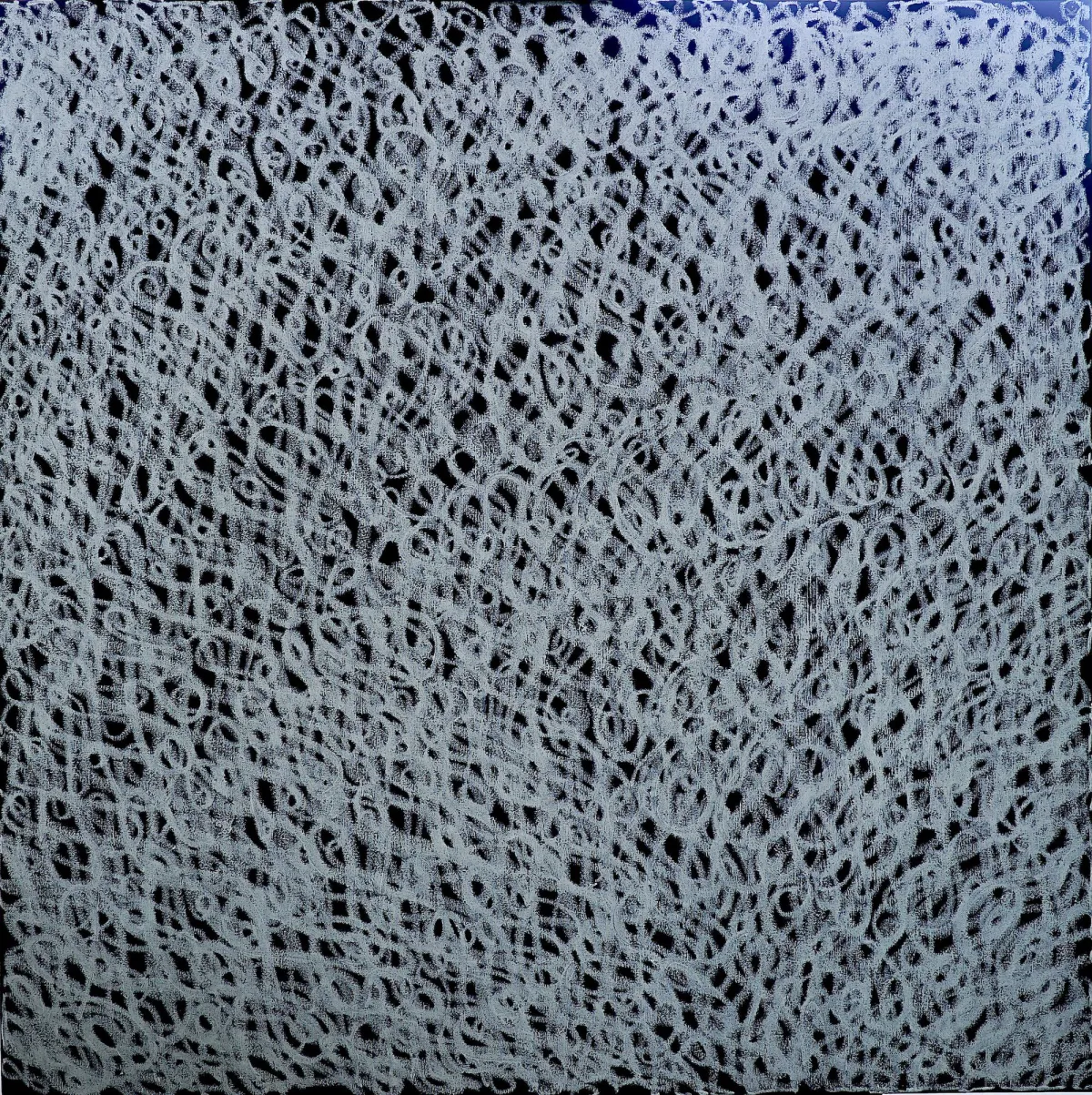

This pattern is the traditional Gadigal weave as researched with the assistance of the Koori librarians at the State Library of NSW

Foreign friends have often remarked to me in how strange they find it that our trees shed their bark. Our great Yarra (eucalyptus/gum) tell us it’s summer when they crack their outer layer of Bugi like streamers in a ticket-tape parade. It’s like the bark is happily waving to us to venture outside and enjoy the summer sun.

Working with natural ochres and pigments is a joy. This particular piece has been made using an ochre wash made by me from scratch staring with grinding rocks and finishing in a washed application which leaves the canvas looking like timber.

She’s a joy!

Gadigal women. Strong and few.

We come from the smallest kinship post the colony’s inceptions. It’s academically argued that all Gadigal people derive from three people. Im not sure I believe this, but it goes to show how few our numbers dwindled down to.

In spite of such a small kinship, we are Mudung (brave). Showing up

is Mudung in a world that doesn’t want us to identify, speaking up is Mudung in a world that doesn’t want to acknowledge and apologise for the wrongs it has done, and saying NO is Mudung.

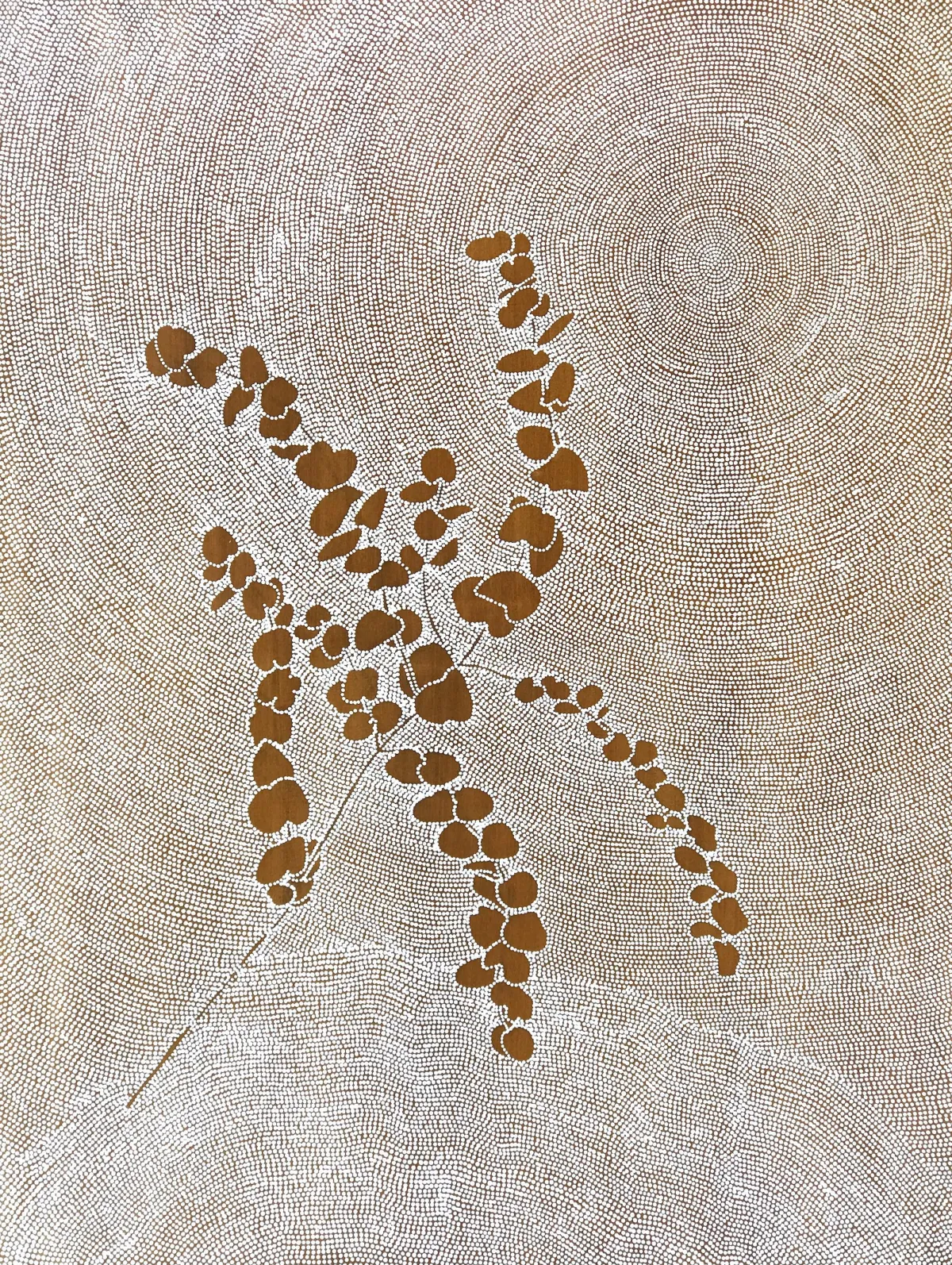

The Yarra are many in number in Eora Nation. One such native, the Eucalyptus Pulverulenta, whose leaves are round and sometimes appear heart shaped, are deliciously fragrant and an original bush medicine for this area. Leaves were picked and used as an antiseptic bed for childbirth and to dress wounds. The sap, which becomes dry and hard, is then ground down into a powder and spread over wounds, sores and even toothaches. This healing plant is just one way our people connect to Country in this area.

This painting is washed with locally foraged Gadigal ochre and overlaid with tiny dots representative of the movement of my people and our spirit of being connected to Country.

Always will be my harbour city home

NGUNUNY is food, is life. Nothing is wasted.

Shell is used for bara (fishing hooks) which the Gadigal dyin (women) invented. Imagine that, us amazing blackfellas - black women invented the commercial / mechanised fishing!

We deliberately laid our midden with the shell of our eating. See, we were the original sustainable farmers. By laying bare our take from Country we were advertising to our kin what had most recently been fished, ensuring that they did not fish the same animal, allowing time for the cycle of life to re-establish itself and ensuring there was no over harvesting and using up the supply. It seems so simple!

Negative Space is a further exploration into my Aboriginal identity, consisting in or characterised by the absence rather than the presence of the distinguishing features making me who I am as an artist, mother, wife and woman.

This is a deeply personal collection which identifies for me the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ of life, spirit and connection to Country through both Aboriginal and White Australian eyes.

Of which, I have both.

For living things ‘To Grow’ new life first we must mature to seed.

Garagula in the original language of the Gadigal people, my people means the ‘ebb and flow of the tide’. There isn’t a phrase that I know of that adequately describes the beautiful patterns of its ripples and land like formations. See for us, the sea, the sky, the land - they are all the same. They are all Ngura (Country), so I guess it doesn’t really matter what its written down as, so long as you can marvel at her beauty.

Since the early days of Colonisation, the positive stories told of the relationship between my people, the Gadigal and those of the broader Eora Nation, have been few and far between. Yet, there was much curiosity and so many genuinely unique experiences for both the British and Aboriginal people to engage in together. This series explorations two unique perspectives on the same subject, as One group believed in linear time, and the other had no construct of such a thing. These Lens’ begin to set up perhaps what went wrong in the later days of the Sydney Colony, and how my people lost their language, the Culture, their Love and unfortunately their Respect.

Since the early days of Colonisation, the positive stories told of the relationship between my people, the Gadigal and those of the broader Eora Nation, have been few and far between. Yet, there was much curiosity and so many genuinely unique experiences for both the British and Aboriginal people to engage in together. This series explorations two unique perspectives on the same subject, as One group believed in linear time, and the other had no construct of such a thing. These Lens’ begin to set up perhaps what went wrong in the later days of the Sydney Colony, and how my people lost their language, the Culture, their Love and unfortunately their Respect.

Since the early days of Colonisation, the positive stories told of the relationship between my people, the Gadigal and those of the broader Eora Nation, have been few and far between. Yet, there was much curiosity and so many genuinely unique experiences for both the British and Aboriginal people to engage in together. This series explorations two unique perspectives on the same subject, as One group believed in linear time, and the other had no construct of such a thing. These Lens’ begin to set up perhaps what went wrong in the later days of the Sydney Colony, and how my people lost their language, the Culture, their Love and unfortunately their Respect.

Since the early days of Colonisation, the positive stories told of the relationship between my people, the Gadigal and those of the broader Eora Nation, have been few and far between. Yet, there was much curiosity and so many genuinely unique experiences for both the British and Aboriginal people to engage in together. This series explorations two unique perspectives on the same subject, as One group believed in linear time, and the other had no construct of such a thing. These Lens’ begin to set up perhaps what went wrong in the later days of the Sydney Colony, and how my people lost their language, the Culture, their Love and unfortunately their Respect.

She is perfection and imperfection. Just like life.

Gadigal people found both beauty and sustenance in all things. The sea snail but one of our treasures.

Gadyan is the original word in my native Gadigal language for the Sydney Cockle Shell.

It said that this shell could be the size of a dinner plate and was aptly found at the site of todays Cockle Bay Wharf’

I have never felt more emotional painting a piece than I have creating this girl.

I’ve connected with my elders on a truly beautiful and meaningful project. I’ve advocated for the fair treatment of other Aboriginal artists, l’ve sat on Country and had prominent corporates and my best mates ask how they help me to champion these Black and White conversations in the year of the Voice.

It has been an utterly overwhelming artist process for this girl who feels today strong and like a woman. Strong in my mind, strong in my culture, strong in my skin and strong in my connection to Eora.

You might know her as Bondi we knew her as Boondi which translated means surf. Or to you she is called Coogee, originally Coojay or the place where seaweed dries, or literal translation “stinking place”. (Bet the real estate agents don’t list that on the brochure).

Whatever name you know her as, Bidjigal Land and the Bidjigal people have always been avid collaborators with my mob, the Gadigal, and those from further away. A hospitable mob who lent their beautiful ocean vistas and plentiful ocean catch to other mob both local and from further afield.

We have all loved Bidjigal Country in some way, and many have called her home over centuries. But it’s little known that the Bondi, Tamarama, Bronte, and Coogee have some of the most amazing free to view Aboriginal rock paintings and engravings of the Eora Nation. You don’t need to go all the way to the desert - they are right there on Bidjigal Country for you all to engage with.

The whale is my favourite and forms a very important part of our Eora Songlines. See if you can find it next-time you’re in the Eastern Suburbs.

My reflection on the white out applied to my dear Aboriginal culture figuratively, metaphorically and spiritually.

A story of the first disposed people of not just the Eora Nation but of all Sahul (Australia). We are now few in numbers, but we were once strong, smart, and full of conciliation. We are a resilient mob, tough and memorable, just as our land is. Otherwise, why would the Colonists have abandoned their designated Colonial site at Botany Bay, to have chosen her banks, her clean water stream, her abundant marine food resource to begin one of the world’s most famous cities.

The Gadigal invented the first fishing hook, and commercial fishing, and we had so many different words to describe love, friendship, and honour, that I can only conclude we used our charm and light to continue our Culture then as we do now. We never gave up, instead we learnt to live within the parameters we were dealt, as we continue to do today. Many of our customs, stories and old ways may be gone, but we are not. Some of the most exciting, exhilarating, and exhausting work I’ve ever produced. Such enormous intensity and measured patience in equal parts as I am Gadigal, and Gadigal is me.

This is my reflection on the white missionary movement in Australia; over-riding or ‘white washing’ the beauty of Aboriginal culture and custom during the long years of colonisation. I am feeling this piece right now. Those were taken, those who were moved to places that were foreign to them, those who were displaced, separated from family and oppressed .. we still feel those effects today! This dislocation of people is Australia’s biggest shame.

As a mother, artist and proud Aboriginal woman, I am obsessed with learning, reading, engaging in and being fully present within my culture. I think it comes from being denied it for such a long time. Regardless

of the why, it allows me to see with fresh eyes the intricacies of our beautiful and old ways.

This piece, which means Country of Languages is cartography of sorts (fancy word for map), it charts, based on early settler maps and accounts the language groups that were represented and where they changed dialect across the greater Eora nation. The place we now call Sydney.

A wildly talented and super smart professor Jakelin Troy has validated these demarcation of language groups in her work Sydney Languages 1994, and notes that whilst all people across this huge space spoken different languages or different dialects of the same language - they could indeed all communicate and comprehend one another.

Isn’t that WILD!

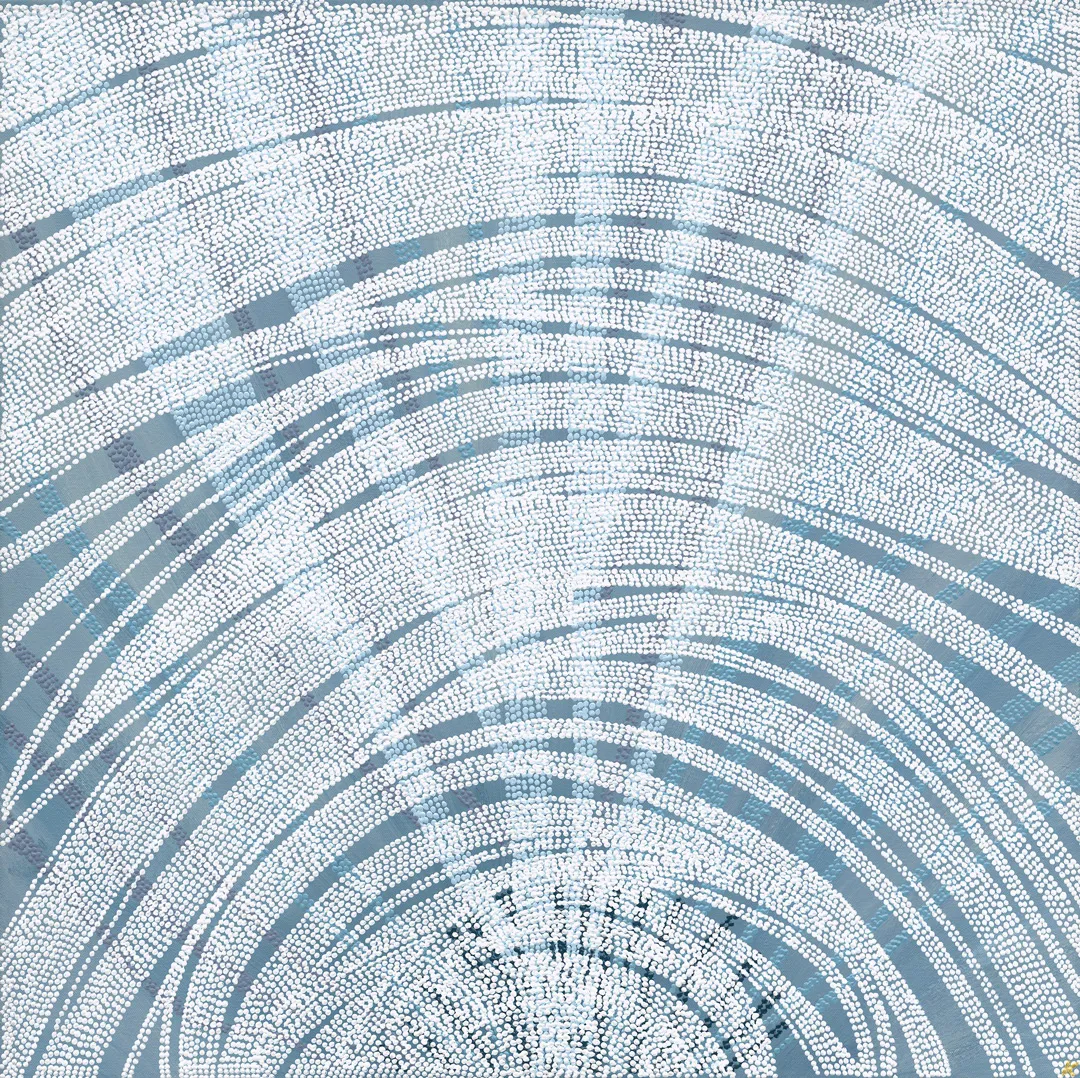

Warrin is part of the Raining Series of works as viewed from my place

in bed, whilst pondering Wiyanga (motherhood), Dyin (womanhood)

and what it’s like to be me. Many Wiyanga feel a stronger connection

to Country and culture after the birth of a child, and for me this piece explore themes of renewal and strength in my Culture, in my Blakness and in my happiness and contentment at being in this moment as a busy Wiyanga of Durung (sons).

Warrin translation of the Gadigal Word into English is Winter. For me I feel the softness of slow morning starts, cuddles in bed and strong hot cups of tea.

She is staunch.

Many people like to say she doesn’t or never existed. I don’t subscribe to that thought. She is home to up to 40 clans.

She ran interference that is not capable of the modern man.

She stopped the “spread” of the Colony for 25 years. 25 years she kept them away! She was harsh on her people, but they knew how to work with her to make her yield.

As the geographical centre of modern-day Sydney, she is often left in the Harbour City’s wake, but her history is immense and well worth looking up.

The Raining Series of works are as viewed from my place in bed, whilst pondering motherhood, womanhood and its like to be a woman. Many mothers feel a stronger connection to country and culture after the birth of a child, and for me this is absolutely the case.

Whilst not technically a language group of her own (Gweagal people belong to the greater Dharawal Mob), this clan is and has always been of great influence in my life. I spent many of my younger years growing up on this Country and she always sang me her stories.

The Gweagal are the traditional owners of the white clay pits in their territory, which are considered sacred. Historically, clay was used to line the base of canoes so fires could be lit inside, and the day’s catch cooked up fresh for the women (who provided the main source of fishing resource) and children.

Caves and rock shelters are located in various places along the Kayimai (Georges River), which over the years have eroded into the sandstone cliffs. There is a large cave located in Peakhurst with its ceiling blackened from thousands of years’ worth of campfire smoke. There are caves located around Evatt Park, Lugarno with oyster shells ground into the cave floor. A cave has also been discovered near a Baptist church in Lugarno which was found to contain ochre and spearheads set into the floor of the cave when it was excavated. Another cave exists on Mickey’s Point, Padstow, which was named after the local Gweagal man. It is thought that the Gweagal clan migrated as far north as Kurnell and west as Liverpool.

This Country feels like my childhood on the Kayimai (Georges River) and is commonly respected as one of the last Sydney Aboriginal frontiers with people living a traditional life up until the early 1900’s.

I’m reminded a lot lately that you need to have both thick and thin skin in the modern world. To be the right balance of emotional resilience and softness and toughness to get through every day.

A dear old friend reminded me recently that we need to hold space for all the experiences in our life (lives) in order to truly accept and appreciate who we are in this moment.

This piece is revealing, layered and exposing. Above al, it feels as it looks, real.